NEGOTIATION SLIDES OUTLINE CHAPTER FIVE

• Perception, Cognition, and Emotion

• Perception, Cognition, and Emotion in Negotiation

The basic building blocks of all social encounters are:

• Perception

• Cognition

– Framing

– Cognitive biases

• Emotion

– Perception

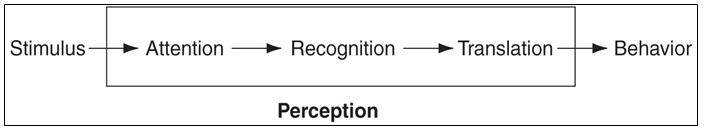

Perception is:

• The process by which individuals connect to their environment.

• A “sense-making” process

• The Process of Perception

• Perceptual Distortion

• Four major perceptual errors:

– Stereotyping

– Halo effects

– Selective perception

– Projection

• Stereotyping and Halo Effects

• Stereotyping:

– Is a very common distortion

– Occurs when an individual assigns attributes to another solely on the basis of the other’s membership in a particular social or demographic category

• Halo effects:

– Are similar to stereotypes

– Occur when an individual generalizes about a variety of attributes based on the knowledge of one attribute of an individual

– Selective Perception

and Projection

and Projection

• Selective perception:

– Perpetuates stereotypes or halo effects

– The perceiver singles out information that supports a prior belief but filters out contrary information

• Projection:

– Arises out of a need to protect one’s own self-concept

– People assign to others the characteristics or feelings that they possess themselves

– Framing

• Frames:

– Represent the subjective mechanism through which people evaluate and make sense out of situations

– Lead people to pursue or avoid subsequent actions

– Focus, shape and organize the world around us

– Make sense of complex realities

– Define a person, event or process

– Impart meaning and significance

– Types of Frames

• Substantive

• Outcome

• Aspiration

• Process

• Identity

• Characterization

• Loss-Gain

• How Frames Work in Negotiation

• Negotiators can use more than one frame

• Mismatches in frames between parties are sources of conflict

• Parties negotiate differently depending on the frame

• Specific frames may be likely to be used with certain types of issues

• Particular types of frames may lead to particular types of agreements

• Parties are likely to assume a particular frame because of various factors

• Interests, Rights, and Power

Parties in conflict use one of three frames:

• Interests: people talk about their “positions” but often what is at stake is their underlying interests

• Rights: people may be concerned about who is “right” – that is, who has legitimacy, who is correct, and what is fair

• Power: people may wish to resolve a conflict on the basis of who is stronger

• The Frame of an Issue Changes as the Negotiation Evolves

• Negotiators tend to argue for stock issues or concerns that are raised every time the parties negotiate

• Each party attempts to make the best possible case for his or her preferred position or perspective

• Frames may define major shifts and transitions in a complex overall negotiation

• Multiple agenda items operate to shape issue development

• Some Advice about Problem Framing for Negotiators

• Frames shape what the parties define as the key issues and how they talk about them

• Both parties have frames

• Frames are controllable, at least to some degree

• Conversations change and transform frames in ways negotiators may not be able to predict but may be able to control

• Certain frames are more likely than others to lead to certain types of processes and outcomes

• Cognitive Biases in Negotiation

• Negotiators have a tendency to make systematic errors when they process information. These errors, collectively labeled cognitive biases, tend to impede negotiator performance.

• Cognitive Biases

• Irrational escalation of commitment

• Mythical fixed-pie beliefs

• Anchoring and adjustment

• Issue framing and risk

• Availability of information

• The winner’s curse

• Overconfidence

• The law of small numbers

• Self-serving biases

• Endowment effect

• Ignoring others’ cognitions

• Reactive devaluation

• Irrational Escalation of Commitment and Mythical Fixed-Pie Beliefs

• Irrational escalation of commitment

– Negotiators maintain commitment to a course of action even when that commitment constitutes irrational behavior

• Mythical fixed-pie beliefs

– Negotiators assume that all negotiations (not just some) involve a fixed pie

• Anchoring and Adjustment

and Issue Framing and Risk

and Issue Framing and Risk

• Anchoring and adjustment

– The effect of the standard (anchor) against which subsequent adjustments (gains or losses) are measured

– The anchor might be based on faulty or incomplete information, thus be misleading

• Issue framing and risk

– Frames can lead people to seek, avoid, or be neutral about risk in decision making and negotiation

• Availability of Information

and the Winner’s Curse

and the Winner’s Curse

• Availability of information

– Operates when information that is presented in vivid or attention-getting ways becomes easy to recall.

– Becomes central and critical in evaluating events and options

• The winner’s curse

– The tendency to settle quickly on an item and then subsequently feel discomfort about a win that comes too easily

• Overconfidence

and the Law of Small Numbers

and the Law of Small Numbers

• Overconfidence

– The tendency of negotiators to believe that their ability to be correct or accurate is greater than is actually true

• The law of small numbers

– The tendency of people to draw conclusions from small sample sizes

– The smaller sample, the greater the possibility that past lessons will be erroneously used to infer what will happen in the future

• Self-Serving Biases

and Endowment Effect

and Endowment Effect

• Self-serving biases

– People often explain another person’s behavior by making attributions, either to the person or to the situation

– There is a tendency to:

• Overestimate the role of personal or internal factors

• Underestimate the role of situational or external factors

• Endowment effect

– The tendency to overvalue something you own or believe you possess

• Ignoring Others’ Cognitions

and Reactive Devaluation

and Reactive Devaluation

• Ignoring others’ cognitions

– Negotiators don’t bother to ask about the other party’s perceptions and thoughts

– This leaves them to work with incomplete information, and thus produces faulty results

• Reactive devaluation

– The process of devaluing the other party’s concessions simply because the other party made them

• Managing Misperceptions and Cognitive Biases in Negotiation

The best advice that negotiators can follow is:

• Be aware of the negative aspects of these biases

• Discuss them in a structured manner within the team and with counterparts

• Mood, Emotion, and Negotiation

• The distinction between mood and emotion is based on three characteristics:

– Specificity

– Intensity

– Duration

• Mood, Emotion, and Negotiation

• Negotiations create both positive and negative emotions

• Positive emotions generally have positive consequences for negotiations

– They are more likely to lead the parties toward more integrative processes

– They create a positive attitude toward the other side

– They promote persistence

• Mood, Emotion, and Negotiation

• Aspects of the negotiation process can lead to positive emotions

– Positive feelings result from fair procedures during negotiation

– Positive feelings result from favorable social comparison

• Mood, Emotion, and Negotiation

• Negative emotions generally have negative consequences for negotiations

– They may lead parties to define the situation as competitive or distributive

– They may undermine a negotiator’s ability to analyze the situation accurately, which adversely affects individual outcomes

– They may lead parties to escalate the conflict

– They may lead parties to retaliate and may thwart integrative outcomes

– Not all negative emotion has the same effect

• Mood, Emotion, and Negotiation

• Aspects of the negotiation process can lead to negative emotions

– Negative emotions may result from a competitive mind-set

– Negative emotions may result from an impasse

– Negative emotions may result from the prospect of beginning a negotiation

• Effects of positive and negative emotion

– Positive feelings may generate negative outcomes

– Negative feelings may elicit beneficial outcomes

• Emotions can be used strategically as negotiation gambits

No comments:

Post a Comment